The steady increase of autistic students entering higher education coincides with schools creating programs and services to meet this growing need. But are these supports working? Autism researchers at Rowan University set out to learn more, and they’ve published their findings in a new book. Read more about their research, recommendations for college success and how their book addresses a growing movement in the autism community.

Three Rowan University authors have collaborated on a recently-published book that could serve as a blueprint for other colleges and universities to better serve autistic students.

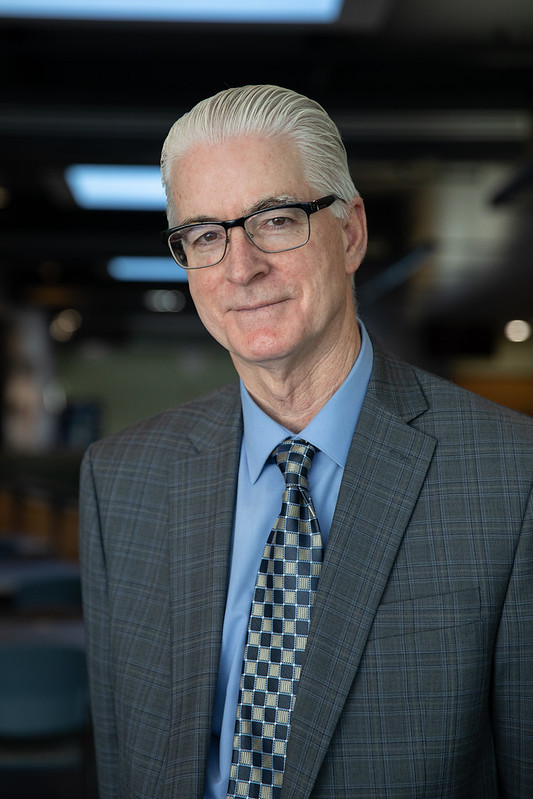

“College Success for Students on the Autism Spectrum: A Neurodiversity Perspective” draws on the research of Dr. S. Jay Kuder, Professor, Department of Interdisciplinary and Inclusive Education and Dr. Amy Accardo, Director of Rowan’s Center for Neurodiversity. The book also outlines practical ways colleges can implement student success programs, many of which are already offered at Rowan under the guidance of John Woodruff, Director of Rowan’s Office of Accessibility Services.

Drs. Kuder and Accardo have long studied autism within the College of Education. John Woodruff has co-authored several research papers with the professors, and the trio have collaborated at Rowan on such projects as a college transition series for prospective students and their families.

The three launched the book project after finding a dearth of national data on college services for autistic students. They found as colleges and universities began building out more programs for a growing population of autistic students, no one entity had evaluated the effectiveness of these supports in the higher education community.

Dr. Kuder says these existing supports, built out of a desire to help students, may possibly be missing the mark; this is compounded by students who either cannot or are reluctant to articulate what they truly want. “This is the need that we saw,” he says.

The purpose, or motivation, of the book, according to Dr. Accardo, “is to help college faculty and staff increase their understanding of the experiences of autistic college students and to put supports in place to increase success for autistic students.”

Drawing from interviews with autistic students and their own data, the authors provide a balanced college guide, blending academic chapters with sections dedicated to the social demands of college life, including mental health. They also cover the transition to and from college as well as career readiness.

Their research inspired a change to the book’s title midway through the writing process.

The authors’ initial aim had been to offer a traditional guide showing colleges how they can “train students to be better students in the classroom, to be better at socialization.” What came from both a movement in the autism community and their own findings was a neurodiversity perspective, which Dr. Accardo explains as “recognizing brain differences as natural human variation,” such as one’s race, gender and sexuality, and “as something to be valued.”

She calls this “a paradigm shift where we value college students with disabilities.”

Dr. Kuder adds, “At some point, we kind of made a major decision to recast our book with more emphasis on strengths of students that students bring, and less on trying to ‘fix’ them.”

Not only did neurodiversity perspective emerge as the book’s subtitle, for the authors, it realigned the whole scope of the project — focusing less on autism’s deficits, stigmas and negative labels and seeing and “celebrating autism as central to identity.”

Through this way of rethinking autism, Dr. Kuder emphasizes colleges should first listen to their autistic students, then develop programming that will support and not aim to just remediate. A large component of this is training faculty and professional staff to be more adaptive — for example, knowing when to adjust programs as needed or when to de-escalate a situation with an upset student. Dr. Kuder stresses the importance of flexibility for faculty and support staff who interface with autistic students. Following trends in the research, he says, “We’ve got to emphasize more understanding and adaptation of the environment to people with autism, rather than try to change them.”

The authors recommend professional development around and faculty/staff training on universal design, a concept derived from architecture. If incorporating elevators and ramps and curb cuts on sidewalks to aid those with physical disabilities helps everyone through universal design, Dr. Accardo explains, colleges could design spaces, classes and courses that may help autistic students but could benefit all learners.

Dr. Accardo also notes their research found higher incidences of co-occurring anxiety and depression among the autistic college community. She recommends students proactively connect with a campus counselor and speak with that same counselor consistently.

“We started working on this before the pandemic, but I think the pandemic sheds a light on the urgency with mental health supports and self care and students with and without disabilities needing to find that balance and to get help when they need it on campus,” Woodruff adds.

The authors added a career readiness portion in the book to combat unemployment and underemployment figures among the autistic college student community. Dr. Kuder confirms that while there is a lack of solid national data on completion rates, “just our own local data tells us that many, many [autistic] students don’t complete college.”

Woodruff was surprised by the lack of research at the onset of this project and wanted to address those areas, particularly with Rowan’s career program specifically for autistic students called PATH. According to its website, the PATH program’s three-pronged approach of career readiness, social engagement and resource networks serve autistic students and alumni for life. Because PATH is also paired with the Office of Career Advancement, the program specializes in job preparation, interviewing skills and resume development.

Dr. Kuder says he has reviewed dozens of college and university-wide programs for autistic students. He recommends parents “look for programs that are emphasizing more supports and accommodations, that are training staff and faculty on how to meet the needs of students with autism.”

Working on this book and with families every day only reaffirmed Woodruff’s belief that for prospective families, “students are the best resource as to [what they] like, what they need, what they don’t need, once they start utilizing the resources.” That last phrase, however, is key. Too many times, Woodruff has seen autistic students try to move through the university with a hidden disability, to not self-disclose nor request accommodations. To parents and guardians, Woodruff says: “I implore you to not let [your students] start college without those resources because what they’re doing is risking a rocky transition to college by abandoning the resources and accommodations that, in many cases, have helped to get them to this point.”

“College Success for Students on the Autism Spectrum: A Neurodiversity Perspective” is available through Stylus Publishing.

Like what you see?

Header photo: John Woodruff (left) and Dr. Amy Accardo (right) co-authored the book, along with Dr. S. Jay Kuder (not pictured)

Related posts:

A Q&A with Terry Nguyen, Co-President of Rowan’s Neurodiversity Club

Ms. Wheelchair New Jersey Lea Donaghy on Advocacy and Education

10 Inclusive Clubs at Rowan University